Author: Norbert Flasko

Reflective Journaling in Social Work Education: A Pathway to Professional Identity Development

The cultivation of a professional identity among social work students represents a critical aspect of their educational journey, one that extends beyond the acquisition of theoretical knowledge and practical skills. It involves a deep, introspective process that integrates personal values, experiences, and beliefs with the core principles of the social work profession. In this context, reflective journaling emerges as a transformative pedagogical tool, enabling students to bridge the gap between personal introspection and professional practice. Einav Segev’s qualitative phenomenological study, conducted with final-year Israeli undergraduate social work students, delves into the multifaceted role of journaling in fostering this professional identity. Through thematic analysis of the students’ reflective journals, the study uncovers the profound ways in which journaling shapes their professional development, providing invaluable insights into its pedagogical significance.

Social work education is designed to prepare students for the complexities of professional practice, equipping them with the ability to navigate interpersonal relationships, address societal inequities, and advocate for vulnerable populations. This preparation necessitates not only the transmission of knowledge and skills but also the cultivation of self-awareness, critical thinking, and reflective capacities. Reflective journaling, as highlighted in Segev’s study, serves as a pivotal medium for this transformative learning process. Despite the extensive literature documenting the benefits of journaling in educational contexts, its specific role in shaping the professional identity of social work students has received comparatively less attention. Segev’s research addresses this gap, focusing on how journaling facilitates the integration of personal experiences with professional knowledge, the internalization of social work values, and the emotional processing essential for effective practice.

At the core of Segev’s findings is the observation that journaling allows students to use their personal experiences as a foundation for constructing their professional identities. This process involves a dynamic interplay between personal and professional dimensions, wherein students reflect on their own life experiences and relate them to the challenges and scenarios they encounter in their training. For instance, students often drew parallels between their personal relationships and their interactions with clients, using these insights to develop empathy and a deeper understanding of their clients’ perspectives. One participant reflected on her experience of ambivalence in her personal relationships, noting how it enabled her to connect with clients facing similar struggles. Such reflections underscore the transformative potential of journaling, as students begin to see their personal narratives not as separate from but as integral to their professional growth.

This integration of personal and professional realms aligns with transformative learning theory, which posits that critical reflection on prior assumptions and experiences fosters profound changes in perspective. Journaling provides a structured yet flexible space for students to engage in this reflective process, allowing them to reconcile their past experiences with their emerging professional identities. For example, students who had previously been clients in therapeutic settings often wrote about how these experiences shaped their understanding of the therapeutic process, enhancing their ability to empathize with and support their future clients. This reflective practice not only deepened their self-awareness but also reinforced their commitment to the principles of social work, such as compassion, respect for diversity, and the pursuit of social justice.

Another significant theme identified in Segev’s study is the role of journaling in helping students acquire and internalize professional concepts and skills. Social work education often emphasizes the importance of linking theoretical knowledge to practical application, a process that can be challenging for students navigating the complexities of fieldwork. Journaling facilitates this connection by providing a platform for students to reflect on the theories and techniques introduced in their coursework and to consider how these can be applied in real-world contexts. Many students described how writing in their journals helped them clarify abstract concepts, such as motivational interviewing or the use of metaphors in therapy, and adapt these to their practical experiences. One student wrote about how the principle of “flowing with resistance” resonated with her, enabling her to approach client interactions with greater empathy and flexibility.

In addition to fostering the integration of theory and practice, journaling serves as a retrospective tool for professional reflection. Segev’s study highlights how students used their journals to revisit past professional encounters, particularly those that had been challenging or emotionally taxing. This retrospective reflection allowed them to gain new insights into their actions, identify areas for improvement, and derive valuable lessons for future practice. For instance, one participant described how revisiting a past client interaction helped her recognize missed opportunities for intervention and develop a more nuanced understanding of the client’s behavior. Such reflections not only enhanced the students’ critical thinking skills but also instilled a sense of professional growth and self-compassion. By acknowledging and learning from their mistakes, students were able to view these experiences as integral to their development as competent and reflective practitioners.

The emotional dimension of journaling, as revealed in Segev’s study, is perhaps its most profound and transformative aspect. Journaling provides a safe and resonant space for students to process the intense emotions that often accompany their education and training. Many participants described their journals as a “mirror,” reflecting their internal struggles, fears, and aspirations. This safe space allowed them to articulate and explore feelings that might have been difficult to express in other contexts, such as the classroom or supervision sessions. For example, one student wrote about the overwhelming emotions she experienced during a classroom exercise, how journaling helped her process these feelings and regain her sense of balance. Others used their journals to confront self-doubt and fear, finding solace and encouragement in the act of writing.

The therapeutic potential of journaling is further exemplified by its role in fostering self-awareness and emotional resilience. As students reflected on their experiences, they gained a deeper understanding of their emotional responses and the factors influencing their behavior. This self-awareness, in turn, enabled them to develop strategies for managing stress and maintaining their well-being, both of which are crucial for sustaining a career in social work. One participant eloquently described journaling as “solving a jigsaw puzzle,” a process of piecing together fragments of personal and professional experiences to create a coherent and meaningful whole. Through this process, students not only prepared themselves for the emotional demands of social work but also cultivated a sense of agency and confidence in their ability to navigate these challenges.

The implications of Segev’s findings for social work education are far-reaching. By incorporating reflective journaling into the curriculum, educators can create a supportive and transformative learning environment that fosters the holistic development of their students. Journaling serves as a bridge between academic learning and professional practice, enabling students to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical skills, reflect on their personal and professional experiences, and develop the emotional resilience necessary for effective practice. Moreover, journaling encourages students to take ownership of their learning, positioning them as active participants in their professional development rather than passive recipients of knowledge.

However, Segev’s study also highlights several limitations and areas for further research. The study’s focus on a single course and its reliance on a relatively small and culturally homogeneous sample of participants suggest the need for broader investigations into the role of journaling in social work education. Future research could explore the experiences of students from diverse cultural backgrounds and educational contexts, as well as the long-term impact of journaling on their professional identity and practice. Additionally, integrating other research methods, such as interviews and focus groups, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the benefits and challenges associated with journaling.

In conclusion, reflective journaling emerges from Segev’s study as a powerful and multifaceted tool for social work education. By facilitating the integration of personal experiences with professional knowledge, fostering the internalization of social work values, and providing a safe space for emotional processing, journaling supports students in their journey toward becoming compassionate, competent, and reflective practitioners. As the challenges facing the social work profession continue to evolve, the importance of cultivating such qualities in future practitioners cannot be overstated. Through the simple yet profound act of writing, social work students can embark on a transformative journey of self-discovery and professional growth, preparing them to meet the demands of their field with empathy, resilience, and confidence.

Threshold Decisions in Social Work: Exploring Theory to Enhance Practice

Decision-making forms a cornerstone of social work, often defined by its complexity and the necessity to navigate incomplete or conflicting information. Social workers frequently face the challenge of determining whether a situation demands intervention or meets criteria for service provision. These critical moments of judgment, often referred to as “threshold decisions,” require an intricate balancing of evidence, context, and professional judgment. This article explores the concept of threshold decisions in social work, using theoretical frameworks to deepen understanding and improve practice.

At its core, a threshold decision is a binary judgment, determining whether a case crosses a predefined line or level, such as the need for protective intervention or eligibility for services. These judgments are rarely made in isolation; they form part of a broader assessment process that involves gathering information, interpreting evidence, and aligning actions with legislative, policy, and cultural standards. The stakes are high, as these decisions often have life-altering implications for individuals, families, and communities. Transparency and consistency are crucial, ensuring accountability and fostering public trust.

Common examples of decision making at a threshold in social work are such as:

- compulsory intervention regarding child protection or safeguarding vulnerable adults;

- mental health emergencies and risk levels;

- eligibility for a support service, and managing needs or risk within services;

- need or risk factors on discharge from hospital;

- criminal justice decisions regarding prison discharge or risk;

- whether or not to offer a (non-mandatory) protective service;

- whether action is required by the service regulator in relation to standards of practice;

- entry into and transfers between services.

Threshold judgments are deeply influenced by shifting societal norms, political pressures, and resource constraints. For instance, in child welfare, the concept of “significant harm” hinges on subjective interpretations of “good enough parenting,” which vary across cultures and contexts. Similarly, in other areas like mental health or elder care, decisions are shaped by dynamic definitions of risk and need. The variability and subjectivity inherent in these decisions highlight the need for theoretical frameworks that provide clarity and structure.

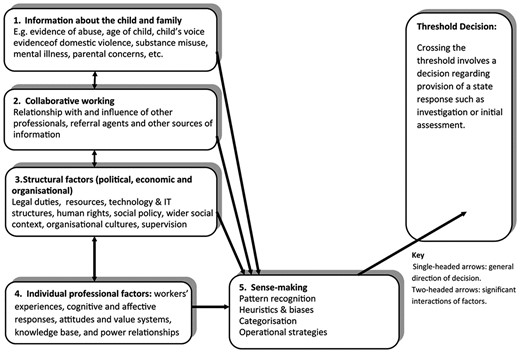

Two key theoretical models illuminate the decision-making process in social work: signal detection theory and evidence accumulation theory. Signal detection theory, initially applied in fields like psychology and medicine, helps practitioners distinguish meaningful “signals” from background “noise.” In social work, this might involve identifying indicators of child abuse amidst a plethora of unrelated information. The theory emphasizes that thresholds are not static; they are influenced by individual and organizational factors, including past experiences, values, and societal expectations. Evidence accumulation theory, on the other hand, conceptualizes decision-making as a process of gathering and evaluating information until a “tipping point” is reached. This approach underscores the cumulative nature of risk assessment, where new evidence can shift the balance and trigger action.

While these models provide valuable insights, they do not fully address the sense-making process that underpins threshold judgments. Naturalistic decision-making (NDM) and heuristic approaches offer complementary perspectives. NDM focuses on how practitioners make decisions in real-world contexts characterized by complexity, time pressure, and high stakes. It emphasizes the role of intuition, experience, and mental shortcuts in navigating uncertainty. Heuristic models, derived from the concept of bounded rationality, highlight the use of simple rules or cognitive shortcuts to manage information overload and make efficient decisions. These approaches recognize the human element in decision-making, acknowledging both its strengths and vulnerabilities.

The interplay between these models reveals the multifaceted nature of threshold decisions. Signal detection and evidence accumulation theories provide a foundation for understanding how evidence is evaluated, while NDM and heuristic approaches offer insights into the cognitive and contextual factors that shape judgments. Integrating these perspectives can enhance our understanding of social work practice, enabling practitioners to navigate the complexities of threshold decisions with greater confidence and effectiveness.

The implications for practice are significant. Understanding the theoretical underpinnings of threshold decisions can improve the transparency and defensibility of judgments, fostering greater accountability and public trust. It also highlights the importance of continuous professional development, enabling social workers to refine their decision-making skills through reflection and learning. Moreover, the integration of theory into practice can inform the development of decision-support tools and training programs, enhancing the overall quality of social work services.

In conclusion, threshold decisions in social work represent a critical juncture where evidence, judgment, and context converge. By exploring theoretical frameworks such as signal detection theory, evidence accumulation theory, NDM, and heuristics, this article provides a comprehensive understanding of these decisions and their implications for practice. As social work continues to evolve in response to societal and technological changes, these insights offer a valuable foundation for advancing professional judgment and improving outcomes for those served by the profession.

The Silent Struggle: Voices of Women Facing Honour-Based Violence and the Role of Swedish Social Services

Honour-based violence (HBV) represents a pervasive form of gendered oppression rooted in cultural traditions and patriarchal systems. It seeks to control and suppress individual agency, particularly for women and girls, in the name of preserving family or community “honour.” This article explores the narratives of young women in Sweden who have endured HBV, shedding light on their vulnerabilities, the systemic challenges they face, and the role of Swedish social services in providing support and relief.

HBV is not confined to a single culture, religion, or region; it transcends borders and manifests in various forms worldwide. At its core, HBV hinges on the belief that the behavior of women is intrinsically tied to the reputation of their families or communities. For the women subjected to these rigid norms, life is often characterized by a lack of autonomy and agency. They are controlled through restrictions on movement, clothing, education, and social interactions, with severe consequences, including violence, when these norms are violated.

In Sweden, a country that prides itself on gender equality and human rights, the existence of HBV underscores the challenges of integrating diverse populations with varying cultural norms. Estimates suggest that tens of thousands of women and girls in Sweden live under the shadow of HBV, facing threats such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and honour-related restrictions. While these numbers highlight the urgency of the issue, they also reveal the limitations of current systems in addressing such deeply ingrained cultural practices.

The study at the center of this discussion focuses on young women aged 18 to 25 who sought help from Swedish social services to escape the grip of HBV. Their narratives provide a vivid picture of the oppressive environments they left behind, as well as the struggles they encountered in their pursuit of freedom. The women described their lives as being tightly controlled by family members, with some recounting experiences of constant surveillance. One woman revealed how her every movement was tracked using bus schedules or even GPS devices, leaving her with no personal space or independence.

The pressure to conform to honour norms extended beyond the immediate family, involving the wider community as enforcers of these standards. Women shared stories of being mocked, shamed, or harassed by neighbors or acquaintances for minor acts of defiance, such as not wearing a veil or attending public swimming pools. These acts of resistance, though small, were seen as affronts to the family’s reputation and often triggered severe backlash.

The decision to seek help from social services was, for many, an act of desperation—a choice made in moments of extreme crisis. For some, this decision came after years of emotional and physical abuse, while others were driven to act by the fear of forced marriage or even death. However, reaching out for help was not without its challenges. The women described the immense psychological burden of breaking family ties, knowing they risked permanent estrangement and even violent retribution. One participant recounted how contacting social services led to threats against her life, as her family viewed her decision as the ultimate betrayal.

Swedish social services play a pivotal role in supporting individuals fleeing HBV, yet their effectiveness is often limited by systemic and cultural gaps. While many women expressed gratitude for the support they received, they also shared stories of frustration and disillusionment. Some women experienced delays in accessing services or felt that their situations were misunderstood by social workers unfamiliar with the complexities of HBV. Language barriers further exacerbated these challenges, with one woman describing how her inability to communicate effectively delayed the assistance she desperately needed.

The quality of placements in sheltered housing or foster families also varied significantly. While some women found solace and security in these environments, others experienced isolation and alienation. One woman compared her foster home to a cold, unwelcoming space, where her emotional needs were overlooked in favor of fulfilling basic physical requirements. She poignantly stated that she would have preferred to live in a refugee camp surrounded by loved ones than to endure the loneliness of her placement.

Despite these challenges, social services also provided life-changing support for many of the women. Thoughtful interventions, such as connecting women with peer networks or providing trauma-informed care, made a significant difference. One participant described the profound relief she felt when a social worker took her fears seriously and acted decisively to ensure her safety. Another woman, who had fled a forced marriage, recounted how social services not only provided her with protection but also helped her rebuild her life, describing the social workers as “angels” who gave her a second chance.

The broader societal response to HBV in Sweden, however, remains inadequate in addressing the root causes of this violence. Prevention and education efforts are critical in challenging the patriarchal norms that underpin HBV. Public awareness campaigns, school-based programs, and community engagement initiatives are essential tools in promoting gender equality and empowering individuals to assert their rights. Yet, these efforts must be coupled with robust support systems that prioritize the needs of survivors.

The study also highlighted the importance of recognizing the psychological toll of HBV on survivors. Many women grappled with feelings of guilt, loss, and identity crises as they navigated their new lives. The emotional strain of severing family ties was compounded by the challenges of integrating into a new cultural context. Social services must take a holistic approach to support, addressing not only the immediate safety concerns of survivors but also their long-term psychological and social needs.

Ultimately, the narratives of these women serve as a powerful testament to their resilience and courage. Their stories reveal the immense strength required to break free from oppressive environments and build independent lives. At the same time, they underscore the urgent need for systemic reforms to ensure that social services are equipped to meet the unique challenges of HBV. By listening to the voices of survivors and incorporating their experiences into policy and practice, Sweden can take meaningful steps toward eradicating HBV and supporting the rights and dignity of all individuals.

Relational Trauma: The Enduring Effects of Maternal Imprisonment on Families

The imprisonment of mothers is a multifaceted issue that leaves profound and enduring effects on family structures, relationships, and individual emotional well-being. Sophie Mitchell’s research explores the complexities of this phenomenon, examining the far-reaching consequences of maternal incarceration on children, kinship carers, and the broader family unit. By focusing on relational trauma—a disruption in familial bonds caused by separation and societal stigma—Mitchell sheds light on the hidden struggles faced by these families. This work not only highlights the depth of these impacts but also challenges current criminal justice practices, advocating for more compassionate and relationship-centered solutions.

The rising debate around female imprisonment questions its necessity and the disproportionate harm it causes. Unlike the incarceration of men, the imprisonment of women, especially mothers, disrupts family units in ways that often cannot be repaired. In many cases, women are imprisoned for non-violent or minor offenses, yet the punitive effects are amplified by the emotional and practical upheaval experienced by their children and relatives. Mitchell’s work positions these relational damages as a central issue that policymakers must address when considering the sentencing and rehabilitation of mothers.

Relational theory serves as a foundation for understanding how maternal imprisonment causes harm. This theory suggests that women’s sense of self is deeply intertwined with their relationships. Unlike men, whose social structures often remain intact during imprisonment, women experience profound disruptions to their familial connections. This severance creates what Mitchell terms “relational trauma,” a form of emotional and psychological harm stemming from broken bonds with children, kinship carers, and extended family members. Such trauma is not confined to the incarcerated mothers but radiates outward, affecting generations and perpetuating cycles of emotional distress and social disadvantage.

A central theme of this research is the unique impact on children, who are often the most vulnerable victims of maternal incarceration. While paternal imprisonment typically allows children to remain in the care of their mothers, only a small fraction—around 5%—of children stay in their family homes when their mothers are imprisoned. Most are placed with grandmothers, other female relatives, or into state care. This sudden displacement uproots their lives, causing significant emotional and psychological challenges. The lack of stability, combined with the absence of a primary caregiver, leaves children grappling with feelings of abandonment and insecurity.

Mitchell’s study brings a much-needed focus to the experiences of older children, a group often overlooked in discussions about maternal imprisonment. Adolescents and young adults face unique challenges, including navigating their own transitions into adulthood without maternal guidance. Many report feelings of anger, resentment, and confusion, often struggling to reconcile their love for their mothers with the stigma and disruption caused by their incarceration. For instance, one mother described her teenage son’s outbursts of anger and difficulty maintaining relationships, showing how deeply the loss of maternal support affected his emotional well-being.

For younger children, the trauma manifests differently. They may not fully understand the circumstances of their mother’s absence, but they experience its effects acutely. Symptoms such as bed-wetting, anxiety, and social withdrawal are common. Mitchell describes the concept of “ambiguous loss,” where children grapple with the absence of their mother despite her psychological presence in their lives. This conflict, compounded by societal stigma, leaves deep scars that shape their emotional development and future relationships.

Kinship carers, often grandmothers, also bear the brunt of maternal imprisonment. These caregivers step into roles they may not have anticipated, often at great personal cost. Financial strain, emotional exhaustion, and physical health challenges are common as they take on the responsibility of raising children in their later years. Many report feeling isolated and unsupported, navigating a system that offers little assistance to non-parental caregivers. Mitchell recounts the story of a grandmother who aged visibly while caring for her grandson during her daughter’s imprisonment, illustrating the toll this role reversal takes on older family members.

The relational strain extends beyond the caregiving arrangement. The incarceration of a mother often fractures relationships between the mother and her own parents or siblings. Grandmothers, in particular, face difficult decisions about whether to shield children from the reality of their mother’s imprisonment or facilitate contact. This dynamic can create tension and resentment, further complicating familial bonds. One participant shared how her mother refused to bring her young daughter to visit her in prison, prioritizing the child’s emotional well-being but deepening the estrangement between mother and grandmother.

Mitchell’s research underscores the enduring impact of these relational fractures, which do not simply heal upon a mother’s release. For many families, the damage is permanent. Mothers returning from prison often face insurmountable challenges in rebuilding their relationships with children and kinship carers. The stigma of incarceration, combined with feelings of guilt and shame, creates barriers to reconciliation. Some children, particularly adolescents, struggle to forgive their mothers, while others feel conflicted about re-establishing a relationship. These dynamics perpetuate cycles of emotional disconnection and relational trauma.

The systemic failures highlighted in Mitchell’s work call for a reevaluation of criminal justice policies regarding mothers. The use of custodial sentences for non-violent offenses must be reconsidered in light of the relational harm caused. Alternatives to imprisonment, such as community-based programs, could offer more compassionate solutions that preserve familial bonds. Countries like Germany have implemented innovative approaches, allowing mothers to care for their children during the day while returning to custody at night. Such programs not only maintain relationships but also provide opportunities for rehabilitation and growth.

In conclusion, Mitchell’s research paints a compelling picture of the far-reaching consequences of maternal imprisonment. By centering relational theory and the concept of relational trauma, her work challenges policymakers to rethink how justice is administered to mothers. The findings highlight the need for systemic changes that prioritize the well-being of families, offering support to mothers, children, and kinship carers as interconnected parts of a fragile ecosystem. In a system that often values punishment over rehabilitation, Mitchell’s work stands as a vital call for empathy, compassion, and a deeper understanding of the human cost of incarceration.

Socio-Digital Challenges for Social Work in the Metaverse

In recent years, the concept of the metaverse has emerged as a transformative digital paradigm, offering a blend of virtual and real-world experiences that challenge traditional notions of social interaction, governance, and community-building. Coined by Neal Stephenson in his seminal work Snow Crash, the term “metaverse” originally described a three-dimensional digital space where avatars engaged in activities paralleling those of the physical world. Over time, advancements in technology have redefined the metaverse, turning it into a multi-faceted ecosystem where millions of users connect, socialize, and create. For the field of social work, the rapid expansion of this socio-virtual domain presents a unique opportunity to redefine its practices while also addressing an array of new social challenges.

The metaverse, driven by advancements in virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mobile technologies, is no longer confined to gaming platforms. Early iterations like Second Life demonstrated the potential for user-driven virtual communities, commerce, and social experimentation. Modern platforms such as Roblox, Horizon Worlds, and Decentraland have further elevated the metaverse’s capabilities, allowing users to engage in immersive, life-like experiences. This evolution is marked by three distinct technological milestones: the shift from solid digital technology, confined to stationary devices, to liquid technology, characterized by portable, mobile experiences, and finally, the gaseous era, defined by seamless integration of miniaturized, connected devices into everyday life. These advancements have created a mixed-reality environment where users continuously navigate between physical and virtual spaces.

For social workers, the metaverse introduces a profound shift in how social issues manifest and are addressed. Traditional social work frameworks, rooted in direct, face-to-face interactions, are being challenged by the deterritorialized nature of virtual environments. The metaverse is not merely an extension of digital social work, where technology acts as a mediator; it is an entirely new field—virtual social work or v-social work—where both the subject and object of intervention reside within the virtual space. V-social work requires the development of innovative methodologies and competences to address unique challenges, such as navigating relationships with avatars, addressing digital inequalities, and ensuring ethical practices in an environment governed predominantly by private corporations rather than public institutions.

One of the most significant challenges is the redefinition of community and individual identities within the metaverse. Unlike physical communities that are geographically bound, virtual communities are dynamic, fluid, and often transnational. This raises questions about cultural and linguistic diversity, governance mechanisms, and the potential for new forms of social exclusion. For instance, while virtual spaces may reduce visible markers of identity such as skin color or physical disabilities, they may also introduce new hierarchies based on digital literacy, economic access to immersive devices, or social media influence. Social workers must remain vigilant in identifying and addressing these emerging vulnerabilities, advocating for inclusive policies that mitigate digital divides and ensure equitable participation.

Privacy and data protection represent another critical area of concern. In the metaverse, users generate vast amounts of data, from behavioral patterns to personal interactions, often under the ownership and control of private companies. This creates ethical dilemmas around data usage, consent, and confidentiality. Social workers operating in this space must develop competences in digital ethics, ensuring that interventions align with principles of transparency, accountability, and respect for user privacy. Moreover, they must navigate the complexities of legal jurisdictions, as virtual interactions may involve participants from multiple countries with varying regulatory frameworks.

The immersive nature of the metaverse also poses risks related to mental health and well-being. While virtual environments can foster social connection and creativity, they can also exacerbate issues such as addiction, social isolation, and body image disorders. The ability to embody customizable avatars may lead to unrealistic self-perceptions, with individuals struggling to reconcile their virtual identities with their real-world selves. Social workers must address these challenges by designing interventions that promote mental resilience, digital literacy, and balanced engagement with virtual spaces. Additionally, the metaverse offers opportunities for innovative mental health solutions, such as virtual counseling centers, support groups, and therapeutic simulations that transcend geographical and temporal boundaries.

Educational and professional training for social workers must adapt to the demands of v-social work. Traditional competences, such as building trust, assessing needs, and planning interventions, require reinterpretation in a virtual context. For example, establishing a trusting relationship with a client in the metaverse involves understanding avatar dynamics and the authenticity of virtual interactions. Similarly, developing intervention plans must account for the unique characteristics of virtual environments, such as their transient nature and reliance on digital tools. Training programs should incorporate modules on VR and AR technologies, digital ethics, and cross-cultural competence to prepare social workers for the complexities of v-social work.

The governance of the metaverse is another area requiring the attention of social work professionals. As private corporations drive the development and regulation of virtual platforms, issues of accountability and equity arise. Social workers must advocate for policies that prioritize the public good, such as access to affordable immersive technologies, safeguards against exploitation, and mechanisms to address online harassment and crime. Collaboration with technology developers, policymakers, and community organizations is essential to ensure that the metaverse evolves as a space that fosters social inclusion and well-being.

Despite these challenges, the metaverse also offers unprecedented opportunities for social innovation. It enables the creation of virtual social services that cater to diverse needs, from addressing bullying in virtual schools to providing employment guidance and skills training in immersive environments. The flexibility of virtual spaces allows for tailored interventions, such as virtual support networks for marginalized groups or interactive workshops that simulate real-world scenarios. By leveraging the potential of the metaverse, social workers can expand their reach, engage with clients in innovative ways, and address systemic issues from a new vantage point.

In conclusion, the metaverse represents both a frontier and a crucible for the evolution of social work. As millions of users embrace virtual environments as integral to their lives, social workers must rise to the occasion, reimagining their practices and redefining their professional competences. The transition to v-social work is not merely a technological adaptation; it is a profound epistemological and ethical shift that demands collaborative efforts, critical reflection, and a commitment to social justice in the digital age. By embracing the challenges and opportunities of the metaverse, social work can continue its mission of empowering individuals, strengthening communities, and fostering a more equitable society, both in the physical and virtual realms.

Learning by Stealth: The Journey of Newly Qualified Social Workers in Hospital Contexts

Hospitals are multifaceted ecosystems where the fast-paced, multidisciplinary nature of care creates a challenging yet rewarding environment for professionals. For newly qualified social workers (NQSWs), navigating the hospital setting is a unique and demanding journey. This article, based on the research of Danielle Davidson and Rosalyn Darracott, delves into the experiences of these social workers as they transition from academic training to professional practice in hospitals. The findings reveal how organizational factors, professional expectations, and personal growth intersect, often compelling NQSWs to “learn by stealth” to adapt to their roles.

Social workers in hospitals occupy an essential but often ambiguous position. Their roles extend beyond the hospital walls, encompassing tasks like discharge planning, bereavement counseling, patient advocacy, and crisis intervention. Despite their contributions, the hospital environment frequently emphasizes the need for swift discharge and task efficiency, sidelining traditional social work values and holistic care approaches. For NQSWs, this reality starkly contrasts the idealized principles instilled during their university education.

Bridging the Gap Between Education and Practice

Entering the hospital setting is akin to being thrust into uncharted waters for many NQSWs. While university programs equip students with foundational skills and values, the practical realities of hospital work can feel overwhelming. Participants in this study likened the transition to “being hit by a truck,” highlighting the mismatch between theoretical preparation and the operational demands of healthcare settings.

The primary challenge for NQSWs lies in reconciling their values with the pressures of hospital practice. The fast-paced environment, organizational imperatives, and hierarchical nature of healthcare often demand a shift away from patient-centered care toward task-focused efficiency. This adjustment can be jarring, with some participants describing how their social work values initially “fell away” as they learned to perform their duties. Only with time and experience were they able to reconnect with these values and integrate them into their practice.

The Concept of “Learning by Stealth”

In the absence of structured learning opportunities, NQSWs frequently resort to covert methods of acquiring knowledge and skills. This phenomenon, termed “learning by stealth,” reflects the challenges of seeking guidance in an environment that prioritizes competence and efficiency. Social workers often avoid asking questions for fear of appearing unprepared, instead relying on observation, mimicry, and self-directed research to fill gaps in their understanding.

Mastering the language and culture of the hospital is a significant aspect of this process. For instance, social workers described Googling medical terms and diagnoses during meetings to avoid admitting their unfamiliarity. Similarly, they observed and emulated experienced colleagues, selectively adopting practices that aligned with their professional aspirations.

While learning by stealth demonstrates the adaptability and resilience of NQSWs, it comes with risks. Without open dialogue and mentorship, there is a danger of perpetuating suboptimal practices and neglecting critical reflection. As one participant noted, social workers risk becoming “sheep,” merely replicating the behaviors of their predecessors without questioning their validity.

Organizational Barriers to Professional Development

The hospital setting poses several organizational challenges that hinder the professional growth of NQSWs. Workload distribution often leaves recent graduates feeling overwhelmed, while more senior practitioners enjoy lighter responsibilities to accommodate administrative duties. The contractual nature of employment further compounds this issue, fostering job insecurity and competition among colleagues. For many NQSWs, the uncertainty of their positions influences their willingness to advocate for patients or invest in their professional development.

This precarious employment environment also affects the quality of supervision and support available to NQSWs. While managers recognize the importance of mentorship, the frenetic pace of hospital work often reduces supervision to operational matters, leaving little room for critical reflection or professional growth. Consequently, NQSWs must navigate their roles with limited guidance, relying on their resourcefulness to adapt to the complexities of their work.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The findings of this study underscore the need for more intentional support and socialization of NQSWs in hospital contexts. Structured programs like the Queensland Health Social Work New Graduate Programme, which aim to bridge the gap between education and practice, represent a step in the right direction. However, these initiatives must balance task-oriented training with opportunities for critical reflection and professional identity development.

Creating a culture of learning within hospitals requires addressing systemic issues such as workload distribution, job security, and supervisory practices. By fostering an environment where NQSWs feel safe to ask questions and engage in reflective dialogue, hospitals can empower social workers to align their practice with professional values and enhance patient care.

Conclusion

The journey of becoming a hospital social worker is fraught with challenges, particularly for those new to the profession. NQSWs must navigate the complexities of their roles while contending with organizational pressures and limited support. Yet, their resilience and adaptability shine through as they develop their skills and identities, often in unconventional ways.

To support this transition, hospitals must prioritize the professional development of NQSWs, providing them with the resources and mentorship needed to thrive. By doing so, they can ensure that social workers not only meet the demands of their roles but also uphold the values and principles that define their profession.

The Psychosocial Work Environment and Its Impact on Mental Health

The connection between workplace stressors and mental health has emerged as a critical area of study, especially as societies shift from manual to non-manual work environments. This transformation, coupled with the regulation of physical and toxicological workplace hazards, has directed attention toward the psychosocial aspects of work and their impact on well-being. The landmark meta-analytic review conducted by Stansfeld and Candy delves deep into these associations, providing a comprehensive synthesis of longitudinal studies to ascertain the relationship between psychosocial work stressors and mental health outcomes.

The psychosocial work environment encompasses various factors that influence mental health. At the heart of this discourse lies the job-strain model proposed by Karasek, which examines two primary dimensions: psychological job demands and decision latitude. These elements determine whether a job is classified as high-strain, low-strain, active, or passive. High-strain jobs, characterized by intense demands and minimal control, are often predictive of mental health challenges, such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue. In contrast, low-strain jobs with fewer demands and higher control levels generally correspond to better mental health outcomes.

The concept of social support at work, as incorporated into the demand-control-support model, underscores the buffering effects of positive interpersonal relationships in mitigating the adverse impacts of high job demands and low control. Similarly, the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model introduced by Siegrist highlights the psychological distress stemming from a mismatch between the effort expended at work and the rewards received, encompassing salary, recognition, and promotion opportunities. Both models underscore the importance of balance in workplace dynamics to safeguard mental health.

Stansfeld and Candy’s meta-analysis, spanning studies conducted between 1994 and 2005, synthesized findings from 11 high-quality longitudinal studies. The results revealed that psychosocial stressors like low decision latitude, high job demands, low social support, and effort-reward imbalance are significant predictors of common mental disorders. The study’s rigor is evident in its methodological approach, which included stringent inclusion criteria, the use of validated measurement tools, and an emphasis on longitudinal data to mitigate biases related to reverse causation.

The analysis indicated that high job strain and effort-reward imbalance were particularly potent risk factors for mental health challenges. Notably, these associations were robust even after accounting for potential confounding variables, such as socioeconomic status and baseline mental health. The findings also pointed to gender differences in the perception and impact of workplace stressors, with men experiencing more pronounced effects of social support deficits and psychological demands compared to women.

Despite the robust evidence presented, the study acknowledged several limitations. The small number of studies included in the meta-analysis posed challenges for subgroup analyses, and potential publication biases could not be entirely ruled out. Moreover, the reliance on self-reported measures of work characteristics and mental health introduced the possibility of response biases. However, these limitations do not detract from the study’s overarching conclusion that the psychosocial work environment plays a pivotal role in shaping mental health outcomes.

The mechanisms underlying these associations warrant further exploration. The stress hypothesis suggests that adverse work conditions trigger neuroendocrine and metabolic changes, which, in turn, contribute to psychological distress. At the psychological level, poor work conditions may erode self-esteem and mastery, mediating the relationship between work stressors and mental health. These mechanisms highlight the bidirectional nature of the work-mental health relationship, where mental health influences perceptions of work, and workplace dynamics affect mental health.

In conclusion, the meta-analytic review by Stansfeld and Candy provides compelling evidence of the significant impact of the psychosocial work environment on mental health. As workplaces continue to evolve, addressing these psychosocial stressors becomes imperative to foster a supportive and health-promoting work environment. Future research should aim to refine measurement tools, explore the interplay of individual vulnerabilities and workplace dynamics, and develop targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of workplace stressors on mental health.

The Role of Knowledge in Shaping Social Work Identity

Social work occupies a uniquely complex and often conflicted space within the realm of professional practice and academic disciplines. Engaging with diverse populations across varied social contexts, social work operates at the intersection of individuals, groups, and state systems. This breadth has created both opportunities and challenges, leading to persistent questions about the profession’s identity and purpose.

Historically, social work has struggled to define itself with the precision often associated with other professions like law or medicine. This lack of a clear knowledge base has frequently led to an identity crisis within the profession. As social workers navigate a landscape shaped by societal expectations, evolving organizational frameworks, and competing professional paradigms, their sense of identity often becomes fragmented.

Professional identity, broadly understood as the constellation of values, attributes, and experiences through which individuals define themselves within a professional role, plays a critical role in fostering belonging and confidence. For social workers, however, this identity is particularly fluid, shaped by a dynamic interplay of personal experience, practice context, and the values of social justice and human rights. Despite the challenges posed by external pressures, such as neoliberal managerialism and fiscal austerity, many practitioners view the profession’s plurality as a strength, offering a distinctive lens through which to engage with society’s most marginalized.

One recurring theme in debates around social work identity is the role of knowledge. Early professional frameworks emphasized a discrete knowledge base as the hallmark of a legitimate profession. Yet, social work’s knowledge remains diffuse, drawing from fields as varied as sociology, psychology, law, and public health. This eclectic foundation can make it difficult to assert professional authority in multidisciplinary environments. However, it also allows for innovative, emancipatory practices that prioritize relational and contextual understanding over rigid technical solutions.

Interviews with social workers in Scotland illustrate these tensions vividly. Participants expressed frustration over the profession’s low social capital compared to more established fields but also highlighted its holistic and iterative nature. Many saw the breadth of social work knowledge as both a strength and a challenge, enabling them to navigate complex social terrains but complicating efforts to articulate their unique contribution. For some, this ambiguity undermined confidence when working alongside professions with more defined boundaries, such as medicine or law.

Nevertheless, social workers consistently emphasized the importance of care as a foundational principle. Whether organizing hospital discharges or advocating for refugees, practitioners viewed their work as deeply relational, requiring not only technical expertise but also moral purpose and empathy. This emphasis on care underscores the profession’s commitment to addressing the “messiness” of human experience—a quality that traditional evidence-based frameworks often struggle to accommodate.

The challenges of articulating a coherent knowledge base for social work also reflect broader societal expectations. In a world increasingly driven by metrics and procedural accountability, the relational and subjective dimensions of practice are often undervalued. Yet, these very qualities are what make social work indispensable in addressing the complexities of modern life. Practitioners frequently navigate spaces that other professions avoid, embracing uncertainty and co-creating knowledge with service users in ways that resist reductionist models.

Ultimately, social work’s identity lies not in its ability to mimic the “hard” sciences but in its capacity to embrace ambiguity, foster connection, and operate ethically within a context of uncertainty. By reframing its “vagueness” as a strength, the profession can validate its unique contributions and empower practitioners to engage confidently with the challenges of twenty-first-century practice. In doing so, social work reaffirms its commitment to care, justice, and the enduring value of human relationships.

Navigating Gender Barriers

Understanding the Motivations, Experiences, and Challenges of Male Social Work Students in a Female-Majority Profession

The gender disparity in social work has long been a topic of discussion, with the field predominantly occupied by women and men forming a significantly small fraction of the workforce. Despite social work’s commitment to equality, anti-discrimination, and anti-oppressive practices, the profession struggles to achieve a balanced representation of genders. Dr. David Galley’s comprehensive study delves into the experiences, motivations, and barriers that influence male social work students in the United Kingdom. By amplifying their voices, the research provides critical insights into addressing gender imbalance and reframing the narrative around men in social work.

The study emerges from an urgent need to examine why males are underrepresented in social work—a field traditionally associated with caregiving, a role often perceived as contrary to societal expectations of masculinity. While the percentage of female social workers increased from 77% in 2010 to over 83% in 2023, the profession has failed to effectively attract men. This ongoing imbalance reflects entrenched gender stereotypes and a broader societal undervaluation of caregiving as a legitimate career for men. Dr. Galley’s work underscores that achieving gender balance in social work is not merely a numbers game but a necessity for the profession to truly reflect the diverse communities it serves.

Galley’s research draws on data from thirty-four male social work students and alumni aged 23 to 51, representing diverse ethnic, sexual, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Using qualitative methods such as semi-structured interviews, surveys, and field observations, the study examines the complex interplay of motivations, experiences, and challenges faced by male students in a profession dominated by women. The findings shed light on recurring themes, including the influence of family, positive role models, career changes, personal ethics, and gender-based barriers.

For many participants, familial influence played a central role in their decision to pursue social work. Raised in families where caregiving professions were valued, these students often drew inspiration from the careers of parents or siblings who worked as teachers, nurses, or social care professionals. Witnessing the dedication and compassion associated with these roles motivated them to follow a similar path. Others were influenced by their own interactions with social workers during pivotal moments in their lives. Participants who had experienced effective and compassionate social work firsthand were inspired to emulate that positive practice. Conversely, those who had encountered poor social work interventions expressed a desire to improve the system and prevent others from enduring similar shortcomings.

A significant subset of participants entered social work as a second career. These individuals, referred to as “pathfinders” in the study, sought to transition from unsatisfying or unstable careers into a profession that offered personal fulfillment and societal contribution. For some, this shift was met with resistance from family members who questioned the decision to leave higher-paying or more prestigious jobs for a field often criticized for its low pay and perceived lack of status. Nevertheless, these career changers found solace in the altruism and meaningful impact inherent in social work.

Despite these motivations, male social work students face numerous barriers. Financial constraints were a prominent concern, with many participants highlighting the prohibitive costs of higher education and the modest salaries associated with social work. Those enrolled in funded programs, such as the “Step-Up” initiative, noted that such support was crucial for making their studies feasible. However, without these opportunities, the financial burden would have deterred many from entering the field.

Another significant barrier was the profession’s perceived low status. Participants criticized the term “social worker,” which they felt failed to capture the complexity and professionalism of the role, suggesting alternative titles like “social practitioner” to enhance its image. This lack of prestige, coupled with societal stereotypes about caregiving as a “female” occupation, further dissuaded men from considering social work as a viable career.

Gender-based challenges were also prevalent. Many participants reported feeling marginalized within academic settings dominated by feminist pedagogies. While they expressed support for feminist principles, they often felt excluded as potential allies in advancing gender equality. Male students described instances where their contributions were undervalued or dismissed, particularly in discussions of gender-related topics such as domestic violence. The pervasive stereotype of male perpetrators and female victims created additional hurdles, with some participants denied placements in domestic violence services due to their gender.

Interestingly, the study also explored how male students navigated their masculinity within the profession. Participants described a spectrum of strategies, from adopting hypermasculine traits to presenting a softer, more empathetic persona. These varied approaches reflect the fluidity of modern masculinities and their potential alignment with social work’s core values. Some participants acknowledged the career advantages their gender might afford, such as the “glass elevator” effect, which propels men into leadership roles. However, they also emphasized the importance of challenging traditional notions of masculinity and promoting equality within the profession.

The study concludes by emphasizing the need for targeted recruitment strategies and policy changes to address the gender imbalance in social work. Early career interventions, particularly in secondary education, could play a pivotal role in reshaping perceptions of social work as a viable and fulfilling career for men. Additionally, rebranding the profession with titles and language that reflect its professionalism and complexity could enhance its appeal to a broader audience.

Dr. Galley’s research provides a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing male participation in social work. By amplifying the voices of male social work students, the study highlights the importance of creating a more inclusive and equitable profession. Addressing the barriers faced by men in social work is not just about achieving gender balance but also about enriching the profession with diverse perspectives and experiences that ultimately benefit the communities it serves.